Grandpa used to pick me up from school and we walked home to Smolenskaya. When we arrived, he immediately started making lunch and would loudly announce every dish: “First course!” he proclaimed, confidently putting a bowl of soup in front of me. Then came the loud “Second course!”—a plate of pea porridge with butter, Grandpa’s favourite dish. His mother, Zinaida Petrovna, my great-grandmother, lunched with us and always asked him to cut her a “tiiiiny piece of bread,” and after she had refused several pieces he cut, he would lose patience and hand her the tiniest crumb. That always made me laugh!

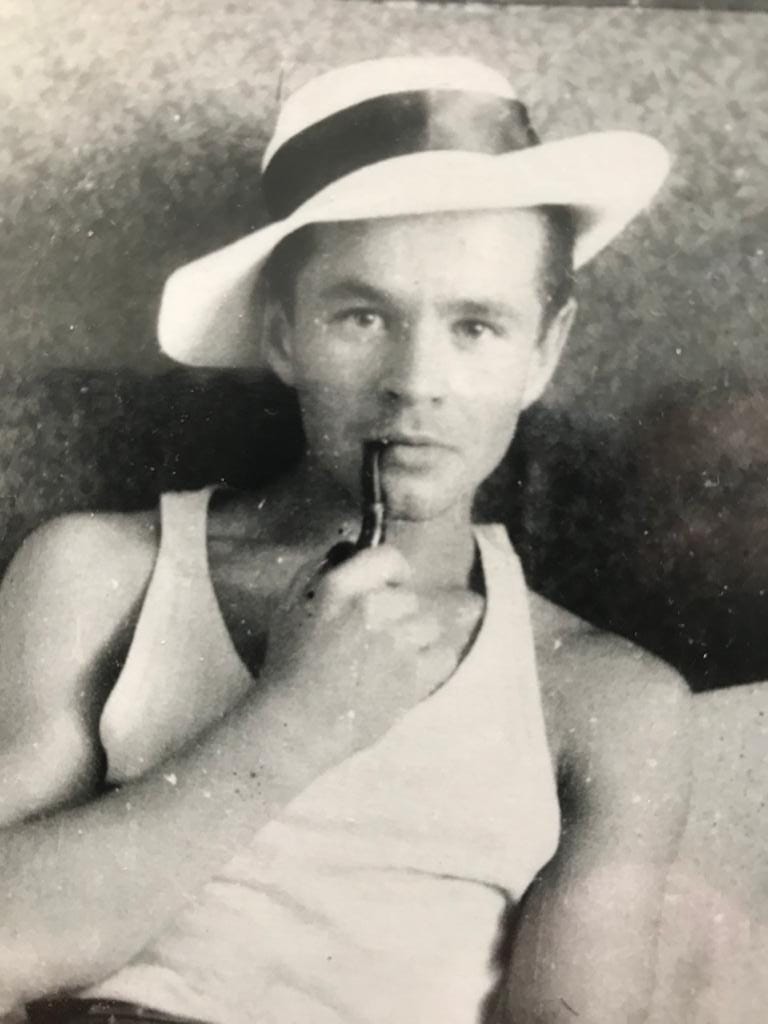

Grandpa did everything briskly, energetically, cheerfully. He didn’t like to fuss around for long, but there was always something mischievous in his manner. Behind his thunderous exclamations came a loud laugh. Grandpa was a great joker.

After lunch, he would let me spend time with him in his workshop—a place absolutely magical for me. Canvases and frames stacked up to the ceiling, a vinyl turntable, records, tapes, notebooks, pens, pencils, chisels, planes, bits of wood—the room was filled with enchantment, mystery, the sense of inventing something extraordinary.

Grandpa was always creating, tinkering, building. Many times I sat on the floor of the workshop, watching him paint, or else repair some device, fine-tune a piece of audio equipment, or even build his own speakers. He would explain to me that his homemade speakers didn’t have three, but four drivers, and that this gave the sound greater depth.

Later, Grandpa would take me into the big room and put on records—The Bremen Town Musicians, Buratino, classical music, as well as singer-songwriters, Soviet and French.

Music filled the house constantly: Grandpa listened to his favourite pieces, but he also recorded programs from Radio Orpheus onto cassette tapes. Each cassette he carefully labeled, placed on the shelves, and catalogued in a big notebook that he kept with great care.

This period of my childhood is inseparably tied to Grandpa, to his magical world. Later, when I was already a student and dropped by his apartment on Smolenskaya, he would ask me about my life and always pose a difficult, slightly embarrassing question: had I found my calling in this life? Now I think that, for him, this was the central question of his own life: free searching, choosing one’s own way. He graduated from Bauman University (an engineering school), but refused to take the government-assigned job and instead joined the Moscow circles of the Sixtiers, painted, and worked as a children’s book illustrator. Grandpa always liked to do things his own way.

And I like to believe I inherited from him that same desire not to do things “the proper way,” but to be playful, mischievous. I love remembering him—his presence, his laughter, our talks about art and about traveling in the Russian North, a journey that, sadly, I never managed to make with him. But studying his works, uncovering new periods and motifs, has become my way of accompanying him on that spiritual journey through Russia—or perhaps, more broadly, on a journey of seeking and discovering one’s own style and spirit.

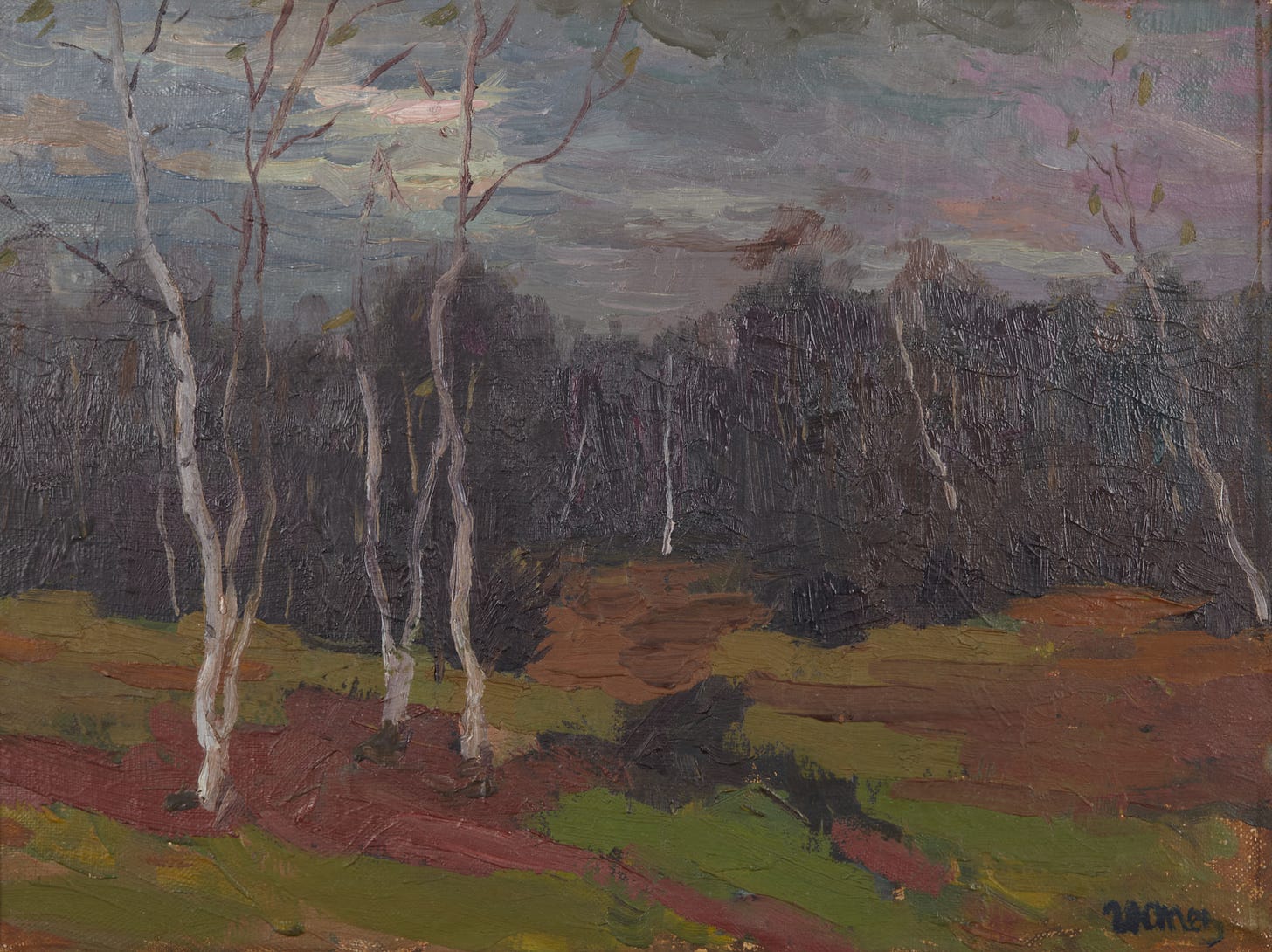

When I failed to give a clear answer to what my vocation was, he would tell me about art, about his own search. At the time, I wasn’t very good at listening to him. It seemed to me that he kept repeating his mantra about the “line of beauty.” Grandpa would say that in his works, he was searching for that line. Like a wave, its curves echoed the shape of the latin S. In his paintings, it traced the outlines of faces, the bends of trees, the contours of houses and churches.

He drew inspiration from icons, from the Russian North, from leaning wooden houses, from a road stretching far into the distance, from shifting light, silhouettes, dawns and sunsets. His works are filled with these images, filled with music.

I think now I see the line of beauty that Grandpa spoke of—the breath of the wave that brings life to everything around it.

Lovely